Cheese, a beloved culinary staple, boasts a rich history and an astounding variety of flavors and textures. But what exactly is normal cheese made of? While different cheese varieties have unique characteristics, the basic ingredients and production process remain surprisingly consistent. Let’s delve into the fascinating world of cheesemaking and uncover the simple yet essential components that transform milk into this delectable treat.

The Building Blocks of Cheese

At its core, cheese is a product of milk, primarily cow’s milk. However, other types of milk like goat, sheep, or buffalo milk can also be used. The magic of cheese lies in the transformation of this liquid into a solid, flavorful form.

Milk: The Foundation

Milk, the star ingredient, provides the proteins and fats that give cheese its unique texture and richness. The type of milk used significantly influences the final flavor and characteristics of the cheese. For instance, cow’s milk yields a milder flavor, while goat’s milk imparts a tangier taste.

Starter Cultures: The Microbial Maestros

These microscopic powerhouses play a pivotal role in cheesemaking. They convert lactose (milk sugar) into lactic acid, which lowers the pH of the milk and initiates the coagulation process. Additionally, different starter cultures contribute to the distinctive flavors of various cheeses.

Rennet: The Coagulation Catalyst

Rennet, an enzyme traditionally sourced from the stomach lining of calves, is another crucial ingredient. It acts as a coagulant, causing the milk proteins to clump together and form curds. Vegetarian alternatives to rennet, derived from plant or microbial sources, are also available.

Salt: The Flavor Enhancer and Preservative

Salt is added to cheese for several reasons. First and foremost, it enhances the flavor and brings out the unique characteristics of each cheese variety. Secondly, it acts as a preservative, inhibiting the growth of unwanted bacteria and extending the cheese’s shelf life.

From Milk to Cheese: The Making Process

The transformation of milk into cheese involves several key steps:

- Pasteurization (Optional): While not always required, pasteurization involves heating the milk to kill harmful bacteria and ensure food safety.

- Acidification: Starter cultures are added to the milk, initiating the conversion of lactose to lactic acid. This acidification process begins to thicken the milk.

- Coagulation: Rennet is added, causing the milk proteins to further coagulate and form a solid mass known as curd.

- Cutting the Curd: The curd is cut into smaller pieces to release whey, the liquid portion of milk. The size of the curds determines the moisture content and texture of the final cheese.

- Cooking and Stirring: The curds are gently heated and stirred to further expel whey and develop the desired texture.

- Draining and Salting: The whey is drained, and salt is added to the curds. The amount of salt added varies depending on the cheese type and desired flavor profile.

- Molding and Pressing: The curds are placed into molds and pressed to shape the cheese and further remove whey.

- Aging (Optional): Some cheeses undergo an aging process, where they are stored in controlled conditions for weeks, months, or even years. Aging allows the cheese to develop complex flavors and textures.

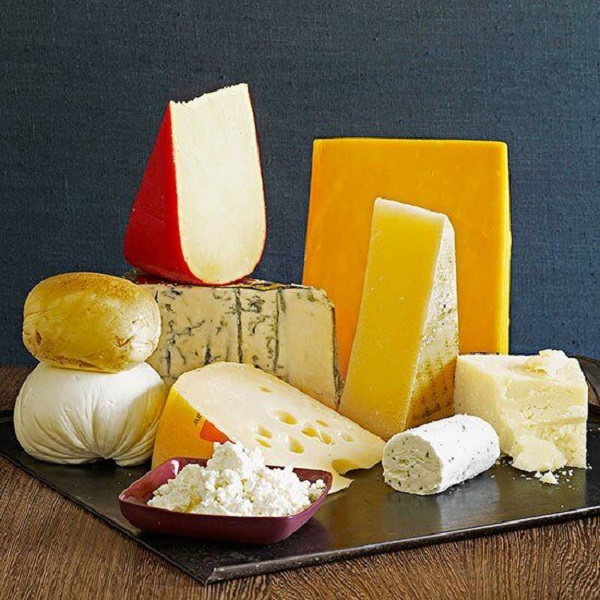

Variations on a Theme: Different Types of Cheese

While the basic ingredients remain consistent, the countless variations in milk type, starter cultures, rennet, and aging techniques lead to the diverse world of cheese we enjoy today.

Fresh Cheeses

- Examples: Mozzarella, ricotta, feta, cottage cheese.

- Characteristics: These cheeses are not aged and have a high moisture content, resulting in a soft, mild flavor and creamy texture.

- Production: They are typically made by directly acidifying milk with starter cultures and adding rennet to form curds. Minimal processing and short aging times preserve their fresh taste.

Soft-Ripened Cheeses

- Examples: Brie, Camembert, goat cheese.

- Characteristics: These cheeses develop a bloomy white rind due to the addition of specific mold cultures. They have a soft, creamy interior and a flavorful rind.

- Production: After initial cheesemaking, they are aged for a short period under controlled humidity and temperature to encourage the growth of the rind.

Semi-Hard Cheeses

- Examples: Gouda, Cheddar, Gruyère, Provolone.

- Characteristics: These cheeses have a firmer texture than soft cheeses but are still pliable. They often have a complex flavor profile due to varying aging times.

- Production: They undergo a longer aging process than fresh or soft cheeses, during which the curds are pressed to remove moisture and develop their characteristic texture.

Hard Cheeses

- Examples: Parmesan, Pecorino Romano, Asiago.

- Characteristics: Hard cheeses have a very low moisture content, making them dense and crumbly.

- Production: They undergo an extensive aging process, sometimes lasting several years, which contributes to their intense flavor and hard texture.

Beyond the Basics: Additional Cheese Ingredients

While the core ingredients remain the same, cheesemakers often add other components to enhance flavor, texture, or appearance.

Flavorings:

Herbs, spices, fruits, nuts, or even smoke can add to impart unique flavors to the cheese.

Colorings:

Natural colorings like annatto (which gives cheddar its orange hue) or paprika can add to adjust the cheese’s appearance.

Other Additives:

Some cheeses may contain additional ingredients like calcium chloride (to improve coagulation) or emulsifiers (to enhance texture).

Cheese: A Nutritional Powerhouse

Cheese is not only delicious but also packed with nutrients.

- Protein: Cheese is an excellent source of protein, which is essential for building and repairing tissues.

- Calcium: It’s also a good source of calcium, a mineral crucial for strong bones and teeth.

- Vitamins: Cheese contains various vitamins, including vitamin A, vitamin B12, and riboflavin.

- Fats: While cheese does contain fat, it’s also a good source of healthy fats that our bodies need.

In essence, “normal” cheese is a simple yet remarkable creation, born from the combination of milk, starter cultures, rennet, and salt. However, the diversity of cheese flavors and textures stems from the myriad possibilities within this basic framework. By understanding the fundamental ingredients and the cheesemaking process, you can appreciate the artistry and science behind every delicious bite of cheese.

Remember, the next time you savor a slice of cheddar, a dollop of ricotta, or a sprinkle of Parmesan, you’re experiencing the culmination of centuries of tradition, innovation, and the transformative power of humble ingredients.

Cheesemaking: An Age-Old Tradition

Different cultures around the world have developed their own unique cheesemaking traditions, resulting in the incredible diversity of cheeses we enjoy today.

Ancient Origins

- Cheesemaking likely originated as a way to preserve milk, as cheese has a longer shelf life than fresh milk.

- The earliest evidence of cheesemaking dates back to around 5500 BC in what is now Poland.

Cultural Significance

- Cheese plays a significant role in many cultures, from the French brie and Camembert to the Italian mozzarella and Parmesan.

- It’s a staple ingredient in countless cuisines, from savory dishes to desserts.

The Science Behind Cheesemaking

Cheesemaking is a blend of art and science. While the basic ingredients are simple, the complex biochemical reactions that occur during the process are fascinating.

Role of Bacteria

- The starter cultures play a crucial role in transforming milk into cheese. They create lactic acid, which lowers the pH of the milk and contributes to the cheese’s flavor and texture.

- Different bacteria strains produce different types of cheeses. For example, the bacteria used in Swiss cheese production creates the characteristic holes.

Rennet’s Action

- Rennet’s enzyme, chymosin, acts on a specific milk protein called casein. It cleaves the casein molecules, causing them to coagulate and form curds.

- The type of rennet used can also affect the cheese’s flavor. Traditional animal rennet produces a slightly different flavor than vegetarian rennet.